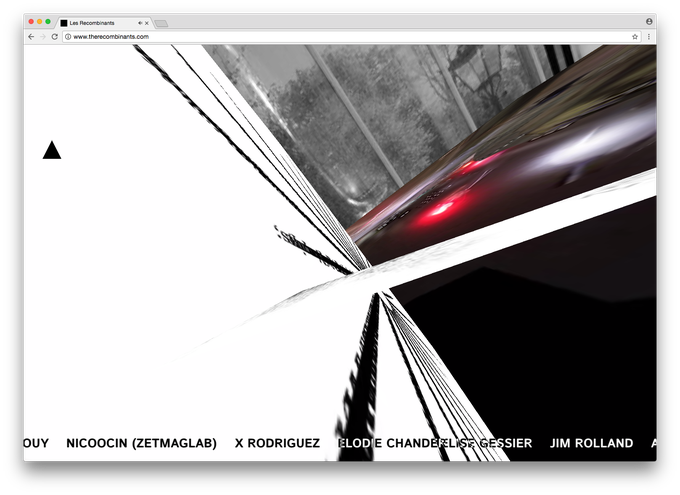

“Les Recombinants”, une exposition d’art en ligne

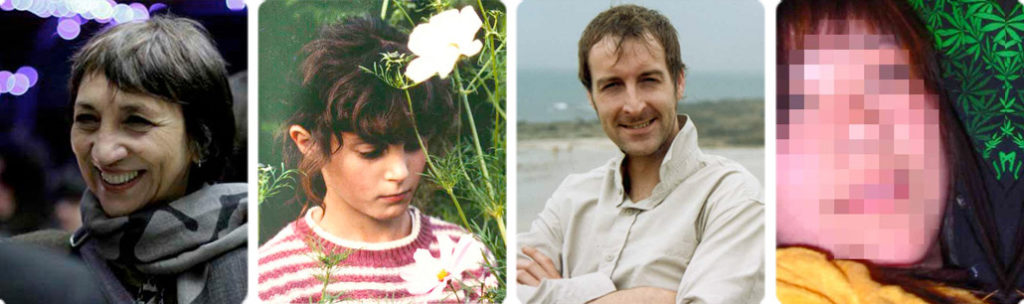

Commissaire d’exposition : Madja Edelstein-Gomez

Une exposition peut-elle être conçue par une intelligence artificielle ?

Ce défi a été relevé par Madja Edelstein-Gomez pour son exposition “Les Recombinants”. Des algorithmes ont choisi des œuvres parmi les centaines de propositions recueillies au cours d’un appel à projet international.

Conçue en temps réel, l’exposition propose un mix hypnotique d’images, de vidéos, de sons et de textes proposés par les artistes et qui se recombinent perpétuellement à l’écran.

Bienvenue chez Les Recombinants, l’exposition du futur.

Autant que leurs œuvres d’art, la personnalité des artistes, leur biographie, la manière dont ils se décrivent eux-mêmes, dont ils montrent leur visage ainsi que leur travail, fait elle-même l’objet d’une recombinance. À l’écran des perspectives diverses s’offrent au visiteur et sur un clic, leur apparence se révèlent lentement, mettant au jour l’arrière-plan de la scène. Sur un clic encore, leurs mots génèrent de nouveaux discours sur l’art et sur l’oeuvre.

Sur le web, vous pourrez expérimenter le traitement des données en temps réel par les algorithmes de l’intelligence artificielle.

Cette découverte individuelle est offerte à votre patience, curiosité et sagacité. En ligne, chaque visiteur verra un spectacle différent, parcourra divers espaces et perspectives des artistes invités par l’intelligence artificielle. Vous pourrez aussi consulter leur présentation individuelle. Assistez à l’oeuvre de ces incroyables robots et découvrez leur pouvoir de calcul instantané ! Devinez leurs mouvements, repérez les œuvres et anticipez leurs combinaisons ! Attention, cela pourrait secouer le navigateur de votre ordinateur et faire fondre votre processeur !

Ce que l’intelligence artificielle démontre est l’extrême compatibilité des artistes. Tous les styles, tous les médias, tous les genres artistiques ont été sollicités et sélectionnés pour être recombinés. Aucune œuvre n’a été jugée trop singulière, exceptionnelle ou hors norme. Aucune n’a été jugée trop démodée, trop laide, trop médiocre ou trop inauthentique. La “sagesse” de l’intelligence artificielle est de rejeter les catégories esthétiques attendues avec leur surcharge historique et sociale et de faire resurgir l’intuition et la sensibilité. Elle réconcilie les spectateurs avec la perception pure. Elle invite les institutions artistiques à s’ouvrir au nouveau monde de l’art, à remettre en question leurs préjugés sur l’art et à repenser ce que peut être une exposition à l’ère du web.

Pour la présentation d’Art-O-Rama Madja Edelstein-Gomez a choisi d’enregistrer trois captures d’écran de quinze minutes chacune. Ces vidéos vous invitent à créer votre propre visite et à découvrir et à expérimenter votre propre spectacle sur votre ordinateur.

Madja Edelstein-Gomez (née en 1960 à Montevideo, Uruguay) est une commissaire d’exposition indépendante , qui a réalisé plusieurs expositions internationales (Bangalore, Buenos Aires, Prague, Tbilisi, Toronto…). Elle vit actuellement à Kuala Lumpur et Paris. Elle est aussi une militante reconnue et engagée auprès de plusieurs associations humanitaires. Site personnel: http://madja.net

L’exposition en ligne est produite par Zinc (Marseilles), avec le soutien financier de : Dicréam-CNC, Château Ephémère (Carrières-sous-Poissy), Espace Gantner (Belfort), Rhizome (New York).

Proud to have Mouchette in this archive!

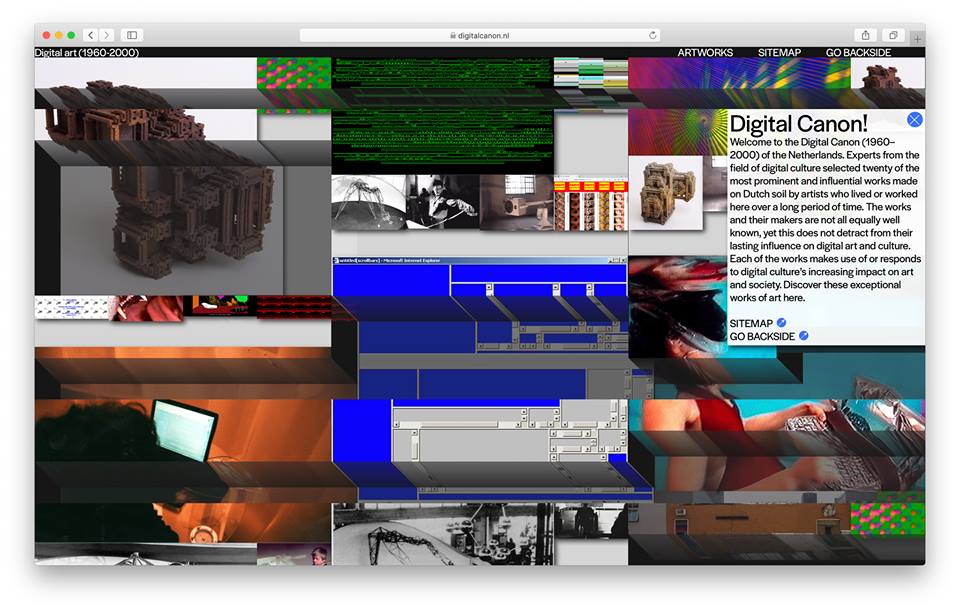

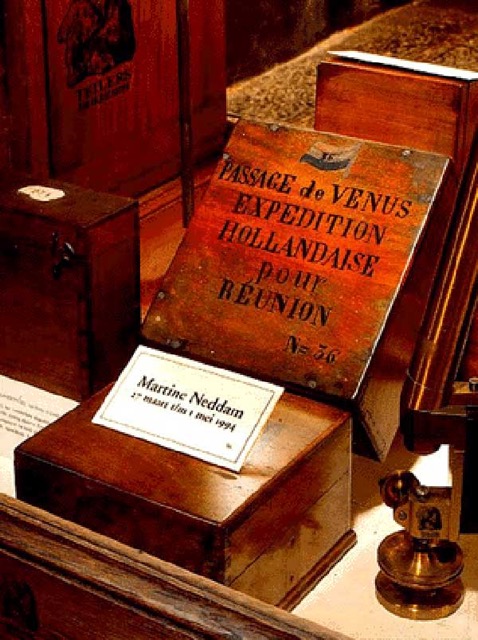

The Digital Canon (1960–2000) of the Netherlands. Experts from the field of digital culture selected twenty of the most prominent and influential works made on Dutch soil by artists who lived or worked here over a long period of time. The works and their makers are not all equally well known, yet this does not detract from their lasting influence on digital art and culture. Each of the works makes use of or responds to digital culture’s increasing impact on art and society. Discover these exceptional works of art here.

Read here why Li-Ma created the Digital Canon

The project has been carried out by a core group (‘the expert group’) and in collaboration with numerous experts from the field. The core team consisted of Josephine Bosma (researcher and critic), Martijn van Boven (artist and tutor), Annet Dekker (researcher and curator), Sandra Fauconnier (art historian) and Jan Robert Leegte (artist and tutor). The project was coordinated by LIMA and supervised by Gaby Wijers (director) and Sanneke Huisman (curator). Additional national and international experts were involved in various international meetings. Together with them, a broadly supported selection was made, while the often authoritarian selection procedures that lie at the basis of canonization were critically reflected upon.The result can be seen on a website dedicated to the project: www.digitalcanon.nl. The twenty canonical works here each have their own page with images, excerpts, videos, quotes from the artists and texts. The works have been researched for this purpose. In addition, the website also contains clear insight into the development of the selection presented and some critical texts about canonizing digital art. The design emphasizes this dual nature by dividing the website into a front and back. This innovative design is made by Yehwan Song. Song is a South Korean designer, web designer and web developer. She designs and develops experimental websites and interactive graphical interfaces. Song is known for her playful design in which she reverses and challenges the general understanding of web design both conceptually and visually.

Follow-up

The canon is by no means an endpoint, but is the starting point for further investigation of the selected works. The first follow-up steps are already being taken. In addition to the website, an exhibition concept will be developed, which involves various relevant issues. For some of the selected works, for example, only documentation material is left and for other works restoration is needed. The canon is also a starting point for discussion and critical reflection, whereby canon formation and the selection procedure are critically examined. The title of the conversation between Josephine Bosma, Martijn van Boven, Annet Dekker, Sandra Fauconnier, Jan Robert Leegte and Gaby Wijers is significant from this point of view: “Canonization as an Activist Act”. The traditional form of canonization is used to open a conversation. The expert group invites the field to make its voice heard. The first external text has already been published on the website: Re-writing the Present: To Inhabit the Inhabitable by Willem van Weelden looks critically and philosophically at (the lack of) historical awareness in the field of canonization and preservation of digital art.

A conversation between Martine Neddam (M) and Annet Dekker (A)

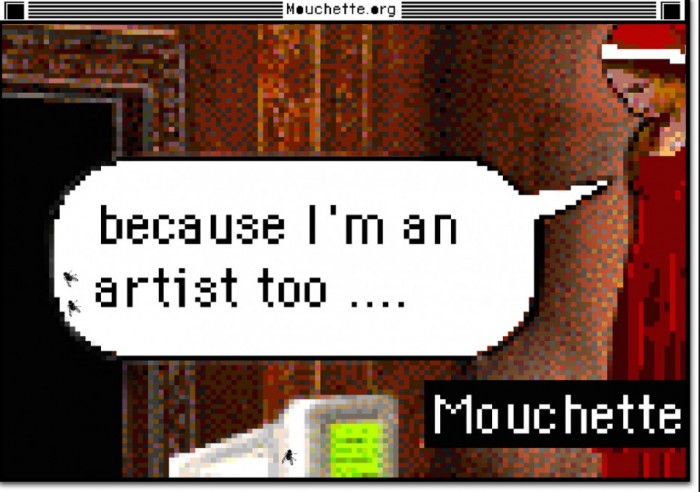

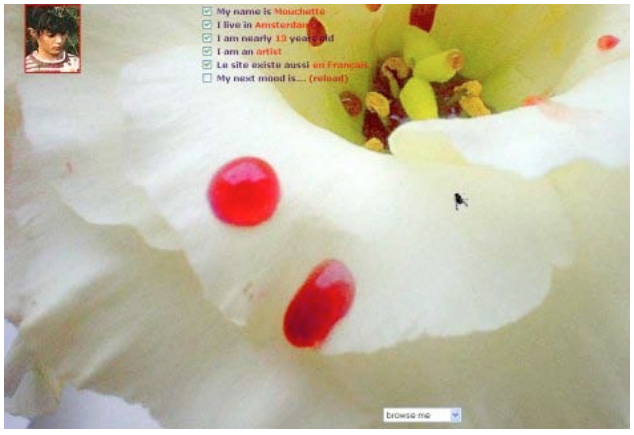

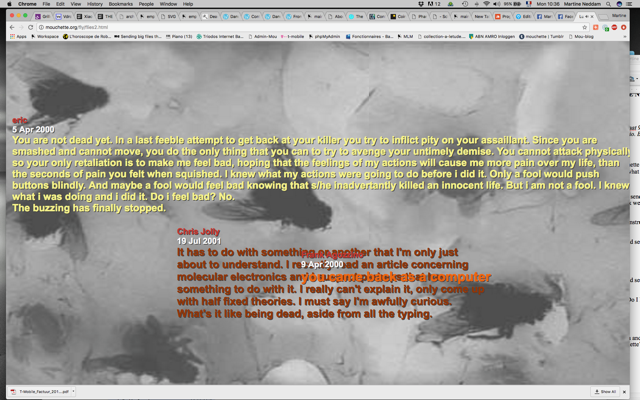

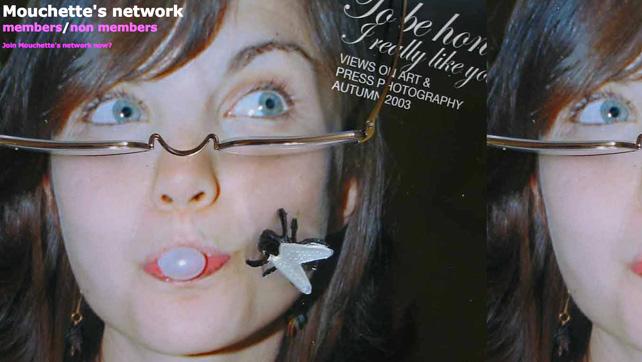

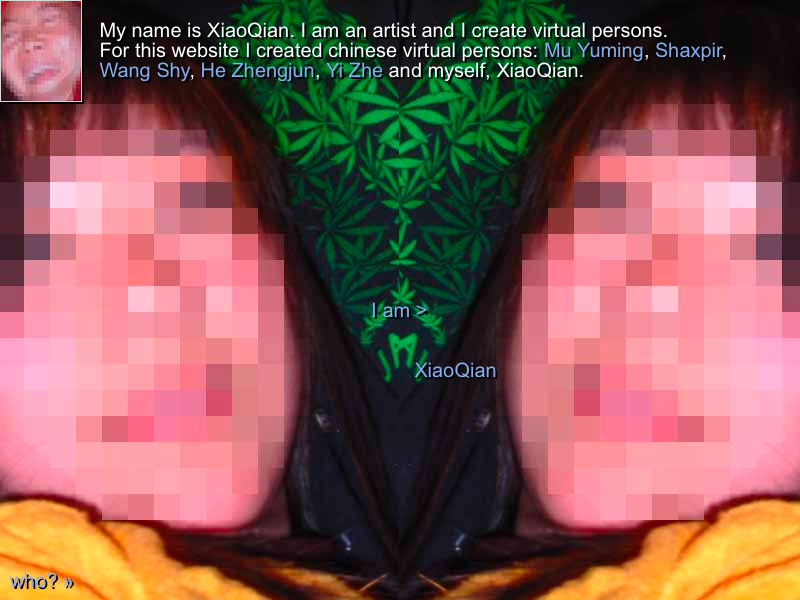

A: When looking back at the website Mouchette.org one could say that it was one of the first fictional personal blogs, a diary of a young girl. But moving beyond that first impression, and looking at the development through the years it has become much more. What does the character of Mouchette mean to you, what does it do?

M: Mouchette was about creating a form and not so much about storytelling. When I started Mouchette I wanted to use the notion of a character as something that transcends mediums, I saw the character as something that can be used as a form, or a container. Using a character as a metaphor allowed me to gather and structure information. I have always believed that a character, a person or an identity is a good metaphor. They can assume the identity of an institution without actually existing. In this sense, I see characters as containers that carry units of meaning.

I was very interested in exploring that idea. At its base, Mouchette shows that identity is a social, mental, or artistic construction. It’s something that you put together. The idea that identity is one thing, ‘Me is one,’ is also an illusion, or a very totalitarian obligation.

A: How did you develop Mouchette? How has it been branded through the years?

M: Many things happened, depending on the works that I put up on the site, but it has never lost popularity. It has a sort of street credibility; in a way people really believed in it and the fake became reality. But the question of whether you’re a real or fake person has become less important now, which is interesting. When I started Mouchette the idea of an alternate persona was still seen as a bizarre phenomenon, so it attracted a lot of attention. Many people posed as characters, for example, mothers would go online pretending to be their daughters, but you only heard of it when they ended up in court, which seldom happened. Through the years and with the rise of popular sites like Second Life it became less and less unusual. It is quite normal to have several e-mail addresses: a work e-mail, a private e-mail, and an old one full of spam, and they represent different personalities in each of us. Everybody has these multiple identities but they didn’t create them in a deliberate way, it just happened.

Whereas in the beginning the question of whether Mouchette existed or not was very important for me, I ended up revealing the true author, but only recently and in quite a low-profile way. Secrecy was a very important part of the work; it really called on the imagination of the reader, the websurfer. While designing the work I kept wondering if the receiver would guess or imagine who was behind the character. For example, I could pretend that Mouchette was a man, but how then could I play out the sexual elements without them becoming perverted? I really emphasised the secrecy and the moments of revelation. I would send a phantom e-mail and pretend that the real author had to reveal his identity and therefore I would name an actual place, a well-known art institution, for example, so that people would believe it.

A: Can you talk a little bit more about these physical presentations? How did you translate the virtual work into the physical world?

M: It was natural for me because I‘ve worked for many years as an artist in public spaces and galleries. It surprised me that when I started Mouchette I was suddenly propelled into the closed field of digital media. This was very limiting for me. I always wanted to present Mouchette in as many ways as possible, always with the website at the centre, and within the context of her personality. Mouchette became the brand through which I presented various projects. I think it had an effect because I know of at least two instances when I was awarded a prize and the jury discussed the secrecy of the artist’s identity, and it really attracted additional attention to the work.

A: Yes, I participated in one of those discussions. It was absolutely fascinating that after so many years, even professionals still discussed Mouchette’s true nature.

M: Yes indeed, but this also happened with writers, famous writers like Romain Gary. And of course it works both ways – it has an influence on the receiver as well as on the author. Hosting another being inside yourself creates certain possibilities that trigger something. I felt it very deeply when I decided to reveal Mouchette’s secret. Mouchette enabled me to escape my grown-up self, to express myself less with words and allow the story to be told more through images. It also allowed me to share parts of my own character that otherwise would not have come out, and to acknowledge that what I wanted to achieve with my art was simply to be famous and loved by everyone.

Sometimes I think that characters exist beyond us; we are merely temporal vehicles or carriers. There were often times when I wanted to get rid of Mouchette because all the work was taking over my life; in a way I was her slave. Martine Neddam the artist was taken over by Mouchette the character, which didn’t even belong to me. Mouchette first appeared in 1937 in a book by Georges Bernanos. Later, in 1967, Robert Bresson made a movie called Mouchette, about a French teenager who commits suicide after she is raped, and I loosely based Mouchette.org on these characters. Others have also used Mouchette.org. So it’s come from somewhere and is going somewhere else and I’m the carrier in between.

A: Is this, for you, also a space where playfulness and irony come into play, the fun side of doing things? Something that is reflected in the projects you create, the coding, the tricks, but also on a conceptual level, a play with language, an urge to transform things, and push limits?

M: Yes, absolutely. It all started with the use of English as a foreign language. In the early days of the Internet people communicated in text spaces, the MOO [ed. MOOs are network accessible, multi-user, programmable, interactive systems, used for the construction of text-based adventure games, conferencing, and other collaborative software and communication platforms]. When I talked with people, I would tell them that English was not my mother tongue, but they would forget this quite quickly, and then my language would come across as very childish. So, there I was in the MOO communicating with MIT people, who were really academic, working on code and text. I was interested in talking to them through a sort of playful interface, which the MOO was. I had this awkward feeling that they would soon forget my ‘accent’ and after two sentences I was just communicating in baby talk, while they were using academic language. Quite unconsciously I was training myself to find simple way to express complex ideas without emotional barriers.

So I decided to take that strategy further with the creation of an online character, Mouchette, who is emotionally very direct but still can communicate ideas about art. This experience was very liberating for me. If I had used my mother tongue it wouldn’t have worked because, like every educated adult, my emotional inhibitions are very strongly rooted inside the language. Using this kind of direct language in a specific way triggered something in me I didn’t know I had. For example, I would say simple phrases like ‘Art is what you say Art is’ using the ‘Duchamp approach’ in a very cheeky way. If I had expressed it in French, I would have used more complex language. Mouchette gave me the opportunity to leave intellectual authority behind. This was important because I wanted to reach another audience that was present on the Internet and move beyond the art gallery and the institutional scene.

For me the irony revealed itself through the aesthetics of the site. Perhaps I can explain it with something I used to say: ‘Can you be pink and conceptual at the same time?’. In the 1970s and 1980s artists from the Art & Language and conceptual art movements were very style driven, even though they pretended that appearance and personality were insignificant. But when look back, it was elegantly black and white, very stylish. Pink at that time, and even now in many cases, wouldn’t be acceptable. Pink is frivolous, not serious; it’s playful and certainly can’t be conceptual or political.

Sometimes this attitude towards the non-pink in art makes me very angry. For example, Mouchette would never be called a political work of art, or even art that engages with the social. At best many art critics and curators see it as a funny little story, non-political and not socially engaged. This has annoyed me at times, because it is political and it does engage with the social on many levels. The idea of alternate identities is very political, as are the notions of multiple identities, and shared identities, which I provided through Mouchette. It’s even more cynical because I’m perhaps one of the few artists who have had to deal with the legal system when I was taken to court. But I also never claimed that it was political or social. I don’t think that’s my role, and it’s not the way the work functions either.

A: Mouchette seems indeed to elude the radars of politics, new technologies and networks, which is regrettable.

M: Yes, it is, but with Mouchette I wanted foremost to create a social space, a space where people could communicate and help other people. Of course, that these things have been sorted, edited and published is in itself a political act. It’s still a sort of repository of thoughts and emotions that wanted to be shared, and finally have been shared. Mouchette shows that art can penetrate people’s private lives, and I believe that is a good thing.

A: You’re pushing the limits of art critics and curators even further, firstly with a Fanclub and now a Guerrilla Fanshop…

M: As soon as I had a mailing list of 20 people I named this list a Fanclub. Over time I noticed that the number of visitors kept growing and that the audience also changed. New people keep on discovering the site. I believe that it’s because of Mouchette’s youthfulness, her combination of energy and anger that is also present in classics such as The Catcher in the Rye. People recognise and identify with Mouchette. For me the Fanshop is a continuation as well as a new step. I like the idea that it is situated in real life. It’s another interesting form for making contact with people. I try to investigate the Fanshop as a social form and an artistic form, including the notions of fake and real. And again, it plays with the idea that an identity can be shared and also be used to offer a platform for different ideas and groups of people.

A: How do you balance between the idea of Mouchette as an identity and as a space where social exchange can take place?

M: The Western world has developed a very limited form of identity, I think. We believe that we can own ourselves, which is absolutely untrue. You’re always a part of something and you switch between different identities. The Western idea of identity needs to be re-examined. I was very aware of that when I created Mouchette. I didn’t want to describe someone, but I wanted to re-examine the conditions of identity as a form of social exchange. I’ve always seen Mouchette as a platform, not as an identity. It, or she, allows me to raise certain issues and also allows others to do certain things. It’s a platform of exchange.

A: And not just of ideas, but also the sharing of identities?

M: Yes, I wanted to put forward the idea of identity as a composition. As I said the notion of a single identity is very artificial; furthermore, whatever identity you do have does not necessarily only belong to you. Its also part of, or even belongs to, everyone who interacts with it. Whatever you do to yourself, for example, if you cut your hair and a friend comes by the next day and is surprised and makes some kind of remark, then that remark could be understood as: ‘You changed yourself without my permission’. I very much like the idea of identity as something that is shared. So I created an identity-sharing interface that made it possible to use or copy Mouchette. Unfortunately, it backfired after the terrorist attack in New York in 2001. I was creating David Still at the time, and was very excited about inventing another character that could be taken over by others. But after terrorism struck, anything that dealt with other identities became suspect. Terrorists could hide behind my characters. Each and every façade was suspect. What was once playful and seductive was made into something to strike out at, something to erase. I really felt that the attack on the Twin Towers and the way America reacted to it threatened my art.

A: How do you see in this light the rise of Facebook? Do you think it might become a way of dealing with different identities again, or a place where people can play with identity?

M: No, exactly the opposite. The whole idea of alternate identities was banned on Facebook. Someone had set up a Facebook page for Mouchette but Facebook shut it down very quickly. They do accept the pseudonyms of famous writers, but if you create three different people with three different e-mail addresses, at some point they will become suspicious and shut down the pages. I’m not entirely sure how they track everything, but building alternate identities is definitely discouraged. Facebook actually started as a virtual dating site, so it’s based entirely on the concept of real identities. If anything, it reinforces the very limited idea of a single identity.

A: What is Mouchette’s next adventure?

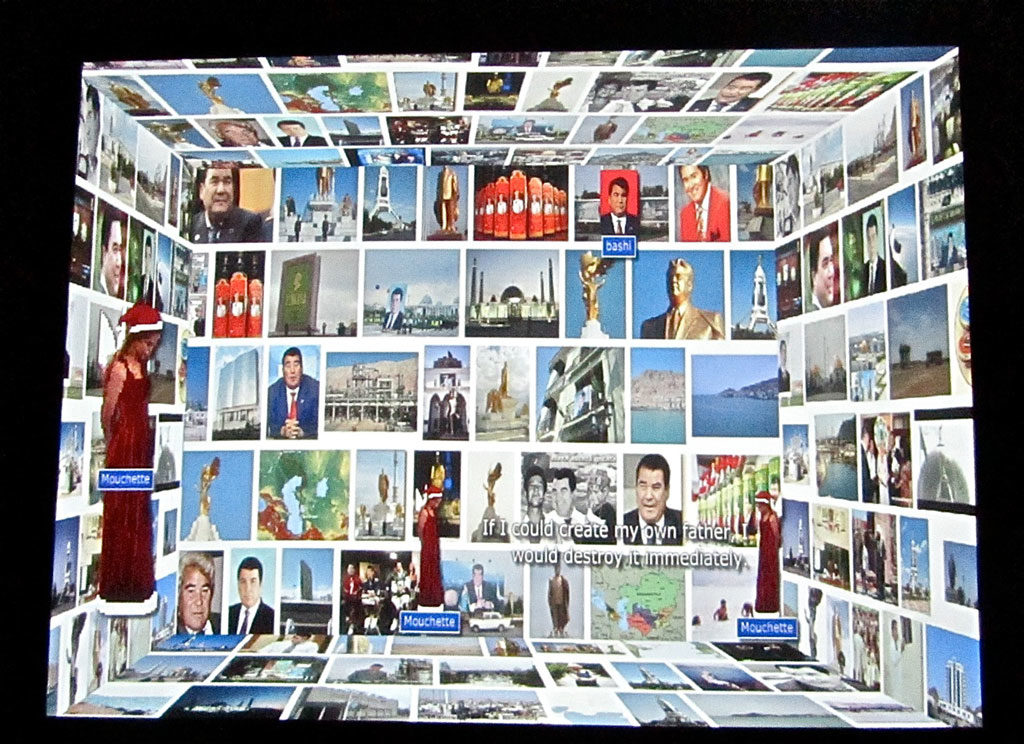

M: I’m still fascinated by made-up characters, especially those that people accept as real. In this line I just finished a work ‘Turkmenbashi, mon amour,’ an animation in which Mouchette shows us Turkmenistan and highlights the presence of its ex-dictator, the late Saparmurad ‘Turkmenbashi’ Nyazov. Even though he’s dead, his personality is still very prominent in the capital, Ashgabat. The city is home to numerous huge golden statues and images of this extremely repressive dictator. At the same time there is a strange atmosphere of non-communication. That tension between his ubiquitous ‘presence‘ and the silence about it was something I wanted to address. So I made a sort of reportage, a documentary with photos and texts, where Mouchette describes and comments in her typically playful and ironic way, addressing the dictator as if she admires him and writing a love letter starting with ‘Turkmenbashi Mon Amour’. Here the play between fiction and reality is to identify these fictional elements in reality, like these crazy self-promoting dictators who are really fictitious characters.

I think I’m bound to continue experimenting with fictitious characters in many different ways, with the ones I invent and with the ones who are already here among us. Once you’ve created one, you realise that our lives are full of them. They are like an army of shadows.

Published in May 2011 in Annet Dekker’s website

This text has been published in the fanzine to be downloaded here

An interview with Martine Neddam by Annet Dekker

You studied literature, language, architecture / décor and sculpture and you have a long career in public sculpture. In the early days of the Internet you created your first virtual character, Mouchette. What made you choose this medium and what interested you so much in the Internet?

My background has always influenced my work, especially the literature studies I undertook in France. I started working as a stage designer after my studies and together with a group of friends we made abstract theatre. The plays were not about the situation, but focused on the presence of the actor and speech. This idea of language, of the act of speech transforming the space is still something I strongly believe in and I have continued working with. For the public commissions I was given I also worked with language and text. As with a theatre play I didn’t necessarily go into what the play said, but interpreted and imagined another perspective for the situation. For example, the space of a square or roundabout is a given and spatially you can’t change much, but by simply renaming the space with a sign you can change the mental perspective people have on it. I also applied this way of working in the gallery and the museum space. Language was my material. I would use expressions and stage them in a certain way. For example, I would write a text on the floor that would only make sense when someone walked on it.

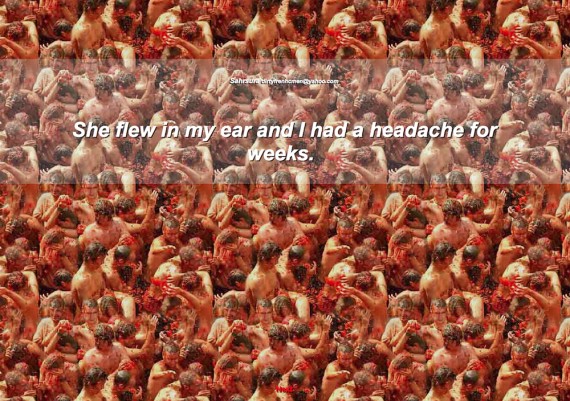

I was quite particular in the type of texts I used, because I was interested in modes of address. I didn’t do poetry or narratives, but confronted people by using the ‘I’ and the ‘you’. Probably affected by my previous experience in linguistics and in stage design, I was very much interested in speech acts and what happens between the sender and the receiver of the message. At times I used offensive text with the purpose of analysing something – not the meaning but the mode of address. I wanted to trigger an emotional response within the safety of the walls of the art institute. Public space was of course much more restricted. But there I very much enjoyed the first hand reactions from people. To me public space has always been about public and less about space. Everything that I made and designed was in relation to a certain public. I regard a public space as a public situation. The work of art is the relation you create between you and your public.

And then the Internet came…

It was fascinating; it was a dream come true. All of a sudden you could address and be addressed. When you create a work you can more or less imagine people’s response in your imagination, but you’re not there when they are doing it. And suddenly there was the possibility of being there when they talk back; being there and not there at the same time. That was utopia, one of very few moments in one’s life when that happens.

How do you see your position in those early days, within that community?

Many people were creating tools to transform the web and they also made them available to others. The web was exciting because it was something you received, and that you could also pass on. It resembled a gift economy and art was more than an aesthetic enterprise. My personal interest was less in creating technical tools and more in analysing forms of communication. I made my first, very primitive web pages in Mouchette in HTML. When users wrote back I would edit that into HTML pages and post them into my site. In 1998 I commissioned an interface with PHP and that result very much resembled a hand-made blog – one of the first blogs. Artists were really on the frontline.

Something I still preserve as precious was the invention of navigation in a text by means of ‘links’, and in that way going from a web page to another web page. ‘Hypertext’ was a word people often used at that time. It showed how much the web was perceived as a modification inside the structure of a text, breaking its linearity. After a while more features were introduced, for example ‘frames’. This made it possible to organise circulation in several pages. I wanted to get the viewer lost in a very complex navigation, where the placement of the links was invisible or unexpected. To me it was very important to keep the web navigation very organic, a mixture of the expected and the unexpected.

This search and interest in the unexpected is something that I don’t see much any more. In the beginning it was everywhere because everything was a surprise. At the moment it seems that few people are on the net to have an unusual experience or to be surprised.

It seems the Internet has lost much of its original energy and optimism. How would you describe the internet at the moment?

Ruled by commercial purposes, with very little private initiative and over designed. Of course it has reached a certain development, especially in the network features and in the way people communicate with each other. But the visual quality and diversity is poor. It is also evolving in a dangerous way because users don’t own their content on most public platforms and it often ends up being used for commercial purposes. Few people are aware of the consequences of Facebook owning their content. Web pioneers were extremely aware of these things. We were asking ourselves moral questions about every interaction because they were new and every action could become an issue and raised questions. That is why it is so important to keep these origins alive because it preserves the traces and the original dreams.

Very few people recognise why the commercial tools are made and to what end. Maybe the role of the artist is to show that. I still see a lot of creative tools made by individual artists and some are very interesting, but they are hardly discussed in fora, even though they are easy to use and could be useful for designers or a general public. Nobody seems to be interested. The biggest problem is the invasiveness of the large companies. The voices of non-commercial innovation are too small to get heard. This is where the small creative networks have to find a solution because huge networks are swallowing them; they get pushed aside and become invisible.

If you look at your different characters, Mouchette, David Still and so on, what is the relationship between them?

With Mouchette I didn’t really have any plans, I just started from scratch: what name do you want to give yourself? Something everyone experiences when you choose an email for example. Starting from that and building up was completely organic. Mouchette was really a mixture of my own fantasy and what the web was becoming. The element of the unexpected was very important in the site and still exists because it has this confusing navigation and it is based on playfullness and surprise.

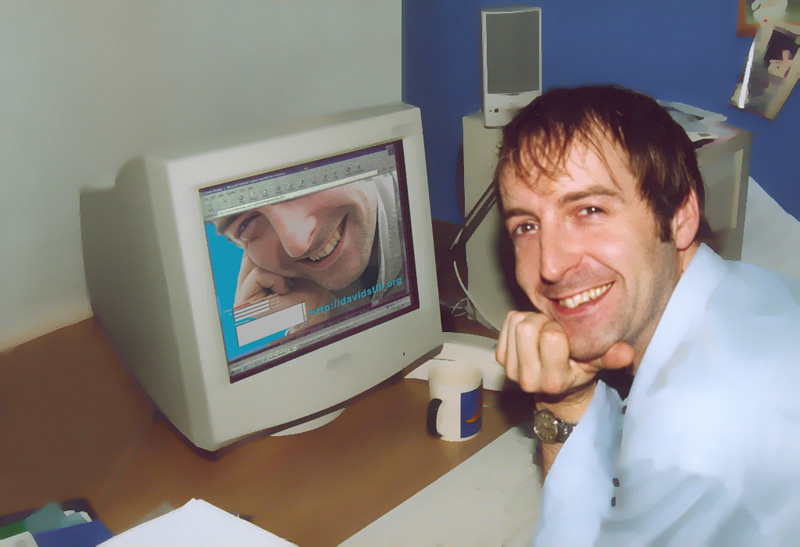

David Still (2001) was a consciously designed tool for a public I knewi. I wanted to observe how people would use this tool. I created David Still both as an online and offline character, as if he lived in the real world. Originally it was a work I did as a public commission for the city of Almere as a representation of the public sphere there . I used certain aspects of the city, like buildings – David Still lives in a street called ‘De Realiteit’ [the reality], which is an architectural experiment in Almere. So it was both reflecting on the public space in Almere as well as on the public space on the Internet.

I had to end David Still’s main function, sending emails from his email address, in 2005 because spam has become such an overwhelming phenomenon that it made it impossible to send messages from an unknown source. Spam started to rule our email exchanges and from that point on David Still was no longer viable – nobody wanted to hear about an unknown person. Different web hosts around the world came up with different legislations against spam and I had to change hosts three times, eventually disabling the send function.

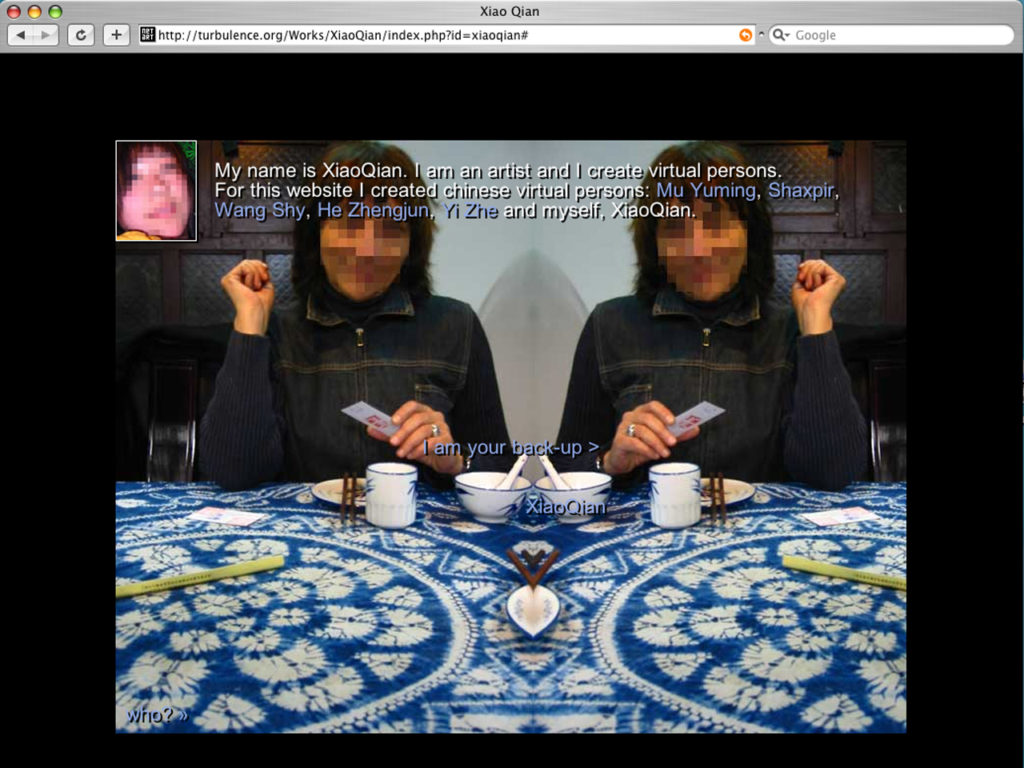

The Virtual Person project that I started in 2008 is also a tool; an experiment with web design and personal expression. The Internet is very much developed as far as networking, dialogue and exchange goes, but there are very few tools for personal expression. Virtual Person.net is a limited tool, because I wanted to make it as accessible and usable as possible. It focuses on certain visual features that I think are meaningful to develop, for example fading one image into another instead of linking them. When you make something with many functions, people use the one by default because there is too much choice, blogs for example are a clear example of this. People who design it say you can do many things with it but users ultimately only use default functions. The result is uniformity.

Most of all by creating VirtualPerson.net I wanted to offer the use of visual features that haven’t been explored; a mixture of text and image in a visual composition. I believe this is an area with huge potential but at the moment texts and images are still treated as separate. They never really merge onto the same surface, contradicting each other or intertwining in a way that creates a different meaning. In Facebook and blogs you can upload image and text separately but it is not possible to combine them in more sophisticated ways. These interfaces are not designed as creative tools. I want to explore the relation between the two in a consistent way. It follows my previous works in the public space and the visual design of Mouchette.

In a way your online work is emblematic of the Internet; reacting to communication systems, issues of identity, spam, image and narrative tools, etc. But also the technical side is highly developed, even though the websites look very easy in set up and design, they were made with state-of-the art technology, mostly adapting and programming existing or new programs and software. Whereas most net_art is known for its innovative use of technology your work is never really mentioned in this respect nor did others ever reflect upon it. Why do you think that is?

I never liked to use technology as the subject of my work. But indeed if you are not interested in technology you can’t work with the web as a medium. From the start I was very close to the new technological developments. Web editing was available to everyone, and when new features appeared in the browser, artists were the first to use them while commercial sites had to wait six months before they could implement them. Artists could create something within half an hour, giving it a certain creative spirit. That may not be the case anymore. At the moment large companies invest huge sums in experimenting and are much faster in finding new solutions than before. But I wouldn’t say that this is innovation: Innovation is not necessarily building on something but it is about questioning, for example how you to not use something. You try to think of something in a different way, that is where innovation comes in.

You made work especially for the Internet, but could you see the work presented on other platforms – pubic (urban screen / mobile phone) or private (gallery/black-white cube)?

Mouchette has always existed in the public space as a collection of different works of art. It wasn’t always easy to exist simultaneously on the Internet and in the world of art. Sometimes I was invited as Martine Neddam and I would ask the museum to present it as Mouchette and to become the accomplice so as to keep the author anonymous. Not everyone accepted, because these were not easy or obvious conditions. But some did and I created installations in the gallery, soundworks, a shopping bag as part of an art manifestation in a shopping mall, etcetera. I used all the existing media and materials available to communicate. I don’t see the Internet as separate from other media, it is just one of the tools. But it still depends very much on my own energy to keep Mouchette connected to the world of art. Most curators don’t think about the possibility of showing art created for the Internet, let alone in another media.

What about using mobile phones, a communication medium that has integrated, text, photo, video and internet, as a platform? It seems an ideal combination.

It is tempting to make special work for mobile phones, but it is still difficult to integrate and to circulate it through various mobile networks. You used to have WAP and Palm, but after one year the technology disappeared. The thing with these mobile devices is that they are enormously controlled and you have to go through so many layers in order to get something out to the public: the whole system is build to limit the possibilities and the creativity of the user. The web wasn’t like that. Suddenly, from one day to the next it was in the hands of the user. That particular freedom is essential if you want to create something.

And what about Urban Screens? People are also referring to them as large communication platforms.

Yes, I would love to experiment with that. For Virtual Person I was tempted to bring it into the public space, and billboards and other screens in the public space seemed a logical place. But there are so many limitations. First of all it would be really difficult to carry out tests and secondly I realised that I would lose intimacy. The physical distance from the body to the screen for example is very important to take into account. It makes a huge difference in impact and experience on the body if you have 1.50m (the television distance) or 50cm for a computer screen, 20 cm for mobile devices or 20 meters minimum with urban screens.

Urban screens have totally different parameters; it is a medium in itself – the distance to the viewer, the scale, the lack of sound, etc. It relates more to billboards and advertising than to internet or mobile phones. Artists have to be commissioned for the situation. Because the advertising space is expensive, it becomes very difficult to experiment freely with the medium and develop a specific language.

How do you see the relationship between the virtual and the real – also in a more bodily/emotional sense? David Still to me was almost tactile, someone very close to you, maybe because he addressed you in a very personal way. Virtual Person is now a tool for making your own Virtual Person.

Virtual Person is about text and image correlation and I would like to make that relation more physical. I am very interested in using touch screens. I would love to embody the connection between texts and images. The act of touching a screen generates a completely different experience than the use of a mouse, even though the use of a mouse is a tactile experience, it emphasizes more directly the bodily experience of the net. I don’t believe that the internet excludes our bodies. Nobody teleports, we still look at the screen using our physical body, with our spine straight or crooked, and with our hand moving and touching. We use our body to inform us about our non-body experience.

Mouchette for example is very much designed from the body on. I would mirror my own situation, my body to the screen, posing an imaginary situation where the viewer and I are mirrored on both sides of the screen, like in the work ‘Flesh&Blood’. When I used sound I recorded it close to the microphone to create that intimacy. The low volume involved the body of the viewer in the act of listening. The Internet is an extension of the body and an out-of-the-body experience, all in one. People tend to say that their body vanishes in the net, but this is precisely that experience that we act out with our body! The fact that your gender is invisible online is a body experience; when does that happen in real life? Many of the early Internet works play precisely with the physical experience of the disappearance of the body. This is why I think it is so important to keep the old examples alive because they bear the trace of the most important discourse on Internet which is still valid but might disappear in the evasiveness of the internet.

As said before, the biggest challenge for the internet today is finding these ‘invisibilities’.

Yes, and in that way I would say that the institutions are not doing their work. They should keep track of these early creations. Some do, like Rhizome, Turbulence or Eyebeam, but there should be more attention in renewing the interest of the public, for example by presenting works again in new contexts or wider contexts.

Another concern is the missing link between the works of net_art and the public. In the beginning the artists did everything by themselves but at the moment that has become more difficult, leading to unstructured relations. This should be one of the tasks of the museums and art institutions and it is not that much work; posting one item a day would suffice. Valuable works of art are already disappearing. Work that I bookmarked two years ago has been taken off because someone did not pay the server costs or the domain registration or couldn’t keep up the maintenance. These are simple things, much cheaper and easier to do than storing a painting or a sculpture in a storage room, and need to be done otherwise many creative possibilities disappear from our landscape and our memory.

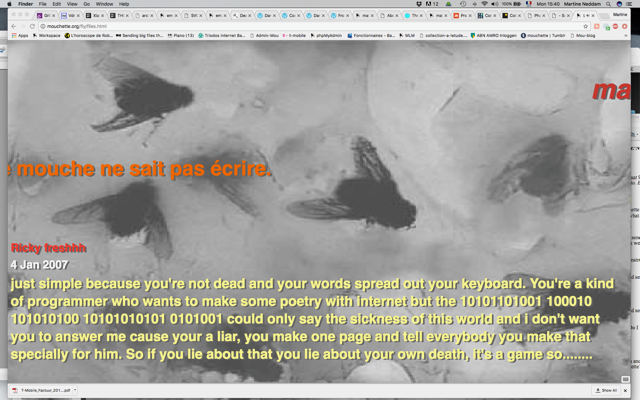

How do you deal with the speed of change on the Internet, especially for your older sites like Mouchette?

There are different levels. Some of the changes are very hard to keep up with, for example the scripts; by changing platforms and operating systems the scripts become less compatible. Suddenly a certain script doesn’t work on a new version of a browser for a certain platform and then some viewers will not see the work as it was meant to be. This is not a new phenomenon, compatibility has always been one of the main issues of the net, but the changes are hard to keep up with. To have a 100% successful viewing you need to create a different version for each configuration, which is a highly technical solution and needs to be re-adapted constantly. I would love to have it done, but I can’t pay for it and at the moment there is no funding for pure maintenance. One year ago I stopped creating new works for Mouchette but I am still working 10 to 15 hours a week to keep it alive, maintaining domains, re-registering etc. If nothing happened the art would die. I have complex scripts that address people one by one and they still function because I know their failures, I keep an eye on it and fix the little mistakes by hand when they happen. It is a very personal use of low technology; everything is made with small pieces of fabric, like a patchwork.

People also regard the internet as virtual, and they believe it means ‘immaterial’ but it is not. Your imagination transforms into actual matter: bits on a server. A computer changes matter into visuals and words. The virtual world consists of bits and pieces: the internet is material, you can break it and make it disappear; that is the reality of the virtual. When you realise how much data Google is saving, that is an enormous conservation of hard disks in large rooms. Maybe when people start to see that the internet is material they might value it more, or treat it in a different way.

i People could send emails coming from David Still to others, thus using his identity.

View the pdf of “In search of the Unexpected”

In Search of the Unexpected, a conversation with Annet Dekker, as a pdf document

2009 navigatinge-culture.PDF is the complete the PDF document. The texte is page 33 to 37

By Martine Neddam,

Your Domain Name Registration Has Expired!

You usually receive several reminders from your registrar warning you about the impending expiry date of your domain name. The first one arrives three months before the date, which is much too early to spend any time on, so you delete that e-mail until, a few weeks later, another warning from your registrar suddenly feels like an emergency threatening to stop everything you’re doing. You grab your credit card and try to renew your registration online.

The warning message, which should have come at just the right moment, never arrived because you had suppressed that old e-mail address, which you thought was only full of spam anyway.

Finally, you remember the expiry date just one day before it’s due. You want to log onto the registrar’s site but you don’t remember which registrar it was. Network Solutions? The one from the Origins? Directnic, the cheapest, you know? Your own webhost? (Most webhosts handle domain name registrations but transfers from other registrars don’t always work.)

You finally work out which of your five different registrars is the correct one, but can’t find the necessary login code and password because you last used it two years ago. You eventually manage to enter the registrar’s interface, but when you want to pay for renewal (three years, that’s the maximum here), your credit card is rejected, and after three attempts, concerned that your credit card number is being hijacked, you stop trying, while your domain name shows no sign of having been renewed.

Your domain name has now expired, and you receive regular warnings, but you can’t find a way to contact this particular registrar, except via the website that refuses your credit card. There, you can use a support page, which sends back automatic replies with a very long code number in the subject header, but this is never followed by a real message written by a human being responding to your complaint.

Your domain name has finally fallen into the hands of ‘domain-name-snatchers’, the resellers of domain names. Now you’ll find a porn site under your domain name, or a webpage promoting the sale of expensive domain names (why isn’t yours included in the list?), or a portal redirecting you to different commercial sites organised by categories.

All your content is still exactly in the same place on your server at the webhost, but nobody will ever be able to find it without your domain name. Search engines won’t be able to find it either, and because of their long-term memory and archives, will remember the old domain name forever. How long will it take you to rebuild your linkage under a different domain name and have the same ranking in the search engines? Will your domain name ever become available for a new registration?

‘Couldn’t connect to database’

You are browsing your site, clicking on a link to review the next entry on a board and suddenly the message ‘couldn’t connect to database’ appears (or a much more obscure message with the same meaning). Your site is there, the top of the page is there, but the dynamic content is no longer accessible.

You become aware that your dynamic content – in other words, the entries of all your users – is stored on a different server, the MySql server, which might be down while your http server is still up and running. You realise that your website is hosted on two separate servers, on two separate hard disks, which doubles your chances of downtime.

As the years go by and your users’ participation continues and your database expands, becoming the most precious part of your art, you are constantly confronted with the many complexities of having a database server.

You have a local copy of your website on the hard disk of your personal computer, including all the html pages, images and Flash files, which is normal since you created all of them on that computer. But your database only exists online on the database server. You can only display your website through an Internet connection and not from a local copy.

Once your webhost went down while you were presenting a lecture about your website at a conference about art on the Internet. Out of desperation you tried to browse your site from your local copy but the pages displayed all the PHP codes instead of the dynamic content. Confronted by all this code and your evident confusion, your audience became really impatient and didn’t even believe you really were the author of a virtual character. Later, you ask your database programmer if you could keep a copy of the database on your hard disk – just in case, even if it’s not up to date – but he explains that the only way to do this is to run a local server, which is far too complicated for you to sort out, especially if you’re using a Mac and it’s pre-OSX, with OS9 not being able to run a local server.

You try to accept the situation but sometimes your relationship with the Internet feels like you are a child depending on its parents, being disconnected for brief moments each day. Sometimes you feel like you are a part of the Internet in the same way that an unborn baby is part of its mother, nourished by the umbilical cord while resting inside a soft bubble.

We don’t accept online documentation

You are assembling your documentation to apply for a grant from the Netherlands Fund for Visual Arts (Fonds BKVB). In their guidelines you read that they accept digital files and websites, but only on a CD-ROM and not online. You call them and insist that your site has a database with important user-generated content and can only run online. They explain that it’s their archival policy to keep and store the information and material from all the artists they sponsor, which is why they requested your website on a CD-ROM. Besides, they want to be 100 per cent certain that the documentation is available for the jury which only meets once a month, so they don’t want to run a risk with your information on a website.

So you decide to make screen snapshots of the database, a large series of pictures that you edit to a proper size in jpg format. You add reference titles and descriptions of the contents and combine all of this in a multiple window website (not online) that you design for the occasion, and it ends up being quite an elegant simulation of the user-generated content that can be browsed online. It is time-consuming work, but the results are good enough and the grant is awarded.

Ultimately you work out that this visual simulation might prove useful, and you decide to always keep a copy of this CD-ROM with you, in your bag, so that you can provide an offline impression of your website at any given moment, on any computer.

But the next time you want to use that CD-ROM, only a year later, you discover that the javascripts supporting the pop-up windows do not function anymore; they have become outdated and are now incompatible with most browsers.

Hopefully nobody at the Fonds BKVB archives will ever look at the contents of your CD-ROM again.

Database back-ups

Your database programmer once made a mistake in which the time-stamp of your entire database was destroyed. All your users’ entries and all the text in your database was still there, in the right categories, but all under one date: 1.1.1970.

This was an incredible disaster, but a very ironic one: you would rather have lost the entire database than just this small ‘piece of time’, which was, you realised, the backbone of a very heterogeneous collection of snippets of texts.

Fortunately, the webhost had a policy of a completely backing-up data every two days and could retrieve a two-day-old version of your database with the time-stamp intact. Just in time, because few hours later the back-up system would have overwritten a new back up with an invalid time-stamp.

That’s when you realised the value of having a back-up system of your own and should no longer rely on the webhost performing miracles.

So, do you have a good automatic back-up system of your own now?

To be honest, you don’t really know….

A good back-up system would automatically store a version of your complete database on a different hard disk every two days, and perhaps save one extra version each month in case of unnoticed damage. You discussed it with Zenuno, a very gentle database programmer who helps you run your server on a volunteer basis. Zenuno works for a Portuguese government website in Lisbon but is based in Amsterdam, and has a great deal of experience in security and back-up issues. You were reassured by his knowledge and his promise that he would set up your back-up system.

Now, writing this, you realise that you haven’t discussed this particular problem with Zenuno since you first raised it, as each time you contacted him since, it was because you needed help with a different emergency, and the back-up issue wasn’t part of that emergency.

So you’re not certain if you have a database back-up system or not, and if you do, you don’t really know what it does.

Recent updates and user complaints

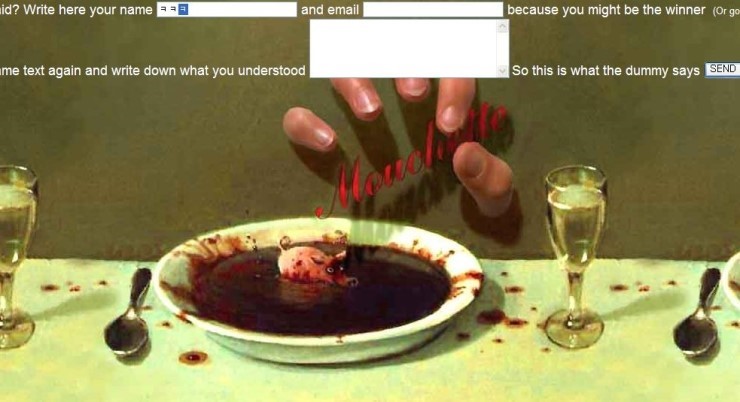

None of the content provided by users of your site is published automatically. Everything you receive, all the reactions to the different works of online art, enters a customized moderator’s interface where you read, classify, publish or delete the entries. When an entry is published the author receives an e-mail informing him of its publication, with a link that enables him to delete his e-mail address from your database, all this wrapped inside a special narrative by Mouchette, written in her house style and related to each online narrative.

You never publish immediately, you always want to wait a few days before you put the text online and notify the author. Your intention is to shape your online relationship with the participating user in order to increase the attention span from a few minutes to a few days. If the delays last too long, a week for example, the attention might be lost and your e-mail becomes a message from an intruder at best; in most cases it is marked as spam and is blocked by the spam filter.

If you go on holiday and decide to avoid all computers for a couple of weeks – which rarely happens – you hope that your users will forget about you in the same way you try to forget about them, but what usually happens is the reverse: you are flooded with complaints and insults about a ‘dead site’ which is ‘never updated’. It’s comforting to know you have such faithful participants. To thank them for their loyalty you immediately publish the complaints about a ‘dead site’, tongue-in-cheek, classified in the ‘favourite’ category, long before you publish the more serious or pleasant entries.

You realise that a number of your participants are ‘hooked’ on your website and you wonder what would happen if you died. How long would it take for them to give up on your site? You think that this could be the measure of the attention span of a dedicated contributor.

On the Internet nobody knows you’re dead…

Like all human beings you’ve doubtless fantasised about your own death. In which ways would you be missed, how you would be remembered, etc.?

As a virtual person you fantasise about how long Internet access to your site and your database system would survive your actual death.

If you died, how long would it take your contributors to realize that nobody is maintaining the site anymore? If they send complaints about a ‘dead site’ nobody will publish them, so the information about the lack of maintenance will not alert anyone. Nobody will know you’re dead.

Sometimes, you start to calculate mentally: ‘My webhosting is paid by the year and is due for renewal in August. My domain registration is paid for two years and is due for renewal in February. The registrar will delete the domain name immediately after expiry but at least the webhost will tolerate one or two months of unpaid hosting before deleting the site. My credit card number is in their system and the webhosting can be renewed at least one more year without my intervention. My credit card is renewed every two years, in January. If I die now, how long will my site stay online and what will be removed first?’

‘After my death how many people will have surfed my site before it is removed?’ This is an easy question and it can have a precise, numerical answer through your web statistics, and long after your site has disappeared, the free statistics (webstats-motigo) site you are using will still provide this information to anyone requesting it.

Who has the codes, or your website, database and server IDs, and who may use them after your death?

Should you leave a will concerning all digital data?

How much of your digital data will stay in the public domain and how much of it do you want to remove?

Shouldn’t you already be erasing your traces?

What kind of peace will you find in your digital afterlife?

Captchas and worms

To prevent unwanted comments from entering your database you can use ‘captchas’ (titbits of warped texts, little visual riddles that can only be solved by a human mind) to block access to automatic scripts. You don’t have them because you couldn’t implement them in your database system, as it was built long before captchas existed. Consequently your database is trashed by several entries arriving automatically each day containing links to Viagra sites or online casinos. None of these are published on your site since you moderate all the entries, and manually delete many of these unwanted entries everyday. Sometimes they arrive as full pages, so you need to read the entire text and recognize that one entry written by a human being among all the spam.

You become infuriated by the amount of time you waste deleting spam. You think that the love of art cannot justify such an absurd daily activity. You sigh…. But sometimes, while doing this, you picture yourself as a gardener sweeping away dead leaves or pulling weeds, and then you smile. Since the battle against spam and nasty scripts is lost and you don’t believe any amount of codes can cure this evil, your last resort is your limitless imagination. While cleaning your database garden you start wondering if any of these unwanted messages have ‘worms’, or are ‘worms’, self-replicating themselves inside your database or replicating the spam message. You groan, your smile has disappeared and you spend the rest of your day reading anti-virus websites finding out about the ‘worms’ in your garden.

Is it art or is it spam?

You were one of the first to integrate the use of e-mail within your artistic practise. To advertise a new work online, your virtual character would send an e-mail recounting a personal story about her life, addressing each recipient by his or her first name.

Your second virtual character was designed to share his identity, and to freely allow the use of his e-mail. He had a website from where you could send his personal stories using his e-mail, and the interface allowed you to personalise the e-mail by placing the name of the intended recipient in the subject line or inserting it in the body of the message.

At some point in the history of the Internet this type of personally addressed e-mail became a very popular device for spammers, who had also noticed how easily they could attract a recipient’s attention by inserting their name everywhere, using this to simulate a one-on-one relationship. After spam filters were improved, they could easily detect this type of subterfuge and many of your art-related e-mails were dumped in your recipients’ e-mail junk folders. And although you had no commercial intentions and your bulk e-mails were very, very modest in quantities, it became very difficult for your art not to pass for spam. And if your webhost received a complaint about spam abuse, he would remove your website. Explaining to your webhost that your e-mails are art, and not spam, couldn’t save the situation. The only option open to you was to move your content to another webhost, until the same problem happened again. Each time the delay before your removal became shorter and after the fourth time, you resolved to stop sending e-mails.

Warning: server space available on earth

It is a common misconception to think of cyberspace as independent of countries or a physical location. Nothing could be farther from the truth. You often think that if your art were destroyed it wouldn’t be because of censorship or related to the content of your information, but because of unfortunate local circumstances: an asteroid could fall precisely where your data is stored at the webhost, and that would be the end of your art. Very unlikely, you admit. But a fire or accident at the place where your webhost has their servers is a possibility, so is criminal destruction, if not targeting you, then possibly someone else who stores their data on the same hard disks. Google is said to have hidden the computers where they save all their users’ data in a secret underground bunker, which makes perfect sense because there must be many people who would like to bomb that location and you could probably imagine yourself as one of them.

Your first webhost, Widexs.nl, was Dutch, located somewhere close to Schiphol (Amsterdam airport), and the servers were probably there too. An airplane never fell on their building, but because all the communication with the technicians was in Dutch, it sometimes added to your worries, especially when a complaint for spam abuse arrived and you had to defend your case with diplomacy. You failed. But you were rescued by a French art group who run their own servers in their own venue. They hosted you for free, being honoured to offer refuge to a banned Internet artist. They said they could afford to ignore the complaints of spam abuse since they ran the servers on their private computers. But one day the server failed. Someone had gone on holiday, leaving his computer on, but locked in a closet for safety’s sake, and everyone had to wait until this person returned from his holidays to re-boot the server. Being hosted on servers run by artists wasn’t the safest option either.

After this episode all you wanted was to go back to a commercial webhost. You combined your efforts with one of the dissatisfied artists from the group who had rented a ‘virtual server’ at Amen.fr, a commercial French webhost. You paid for all the server space while only using a small part in exchange for the artist’s help in running your database and setting the server configurations for you. At the time, you believed you couldn’t cope with these tasks; moreover, the webhost server panels were all in French, which happens to be your mother tongue for everything, except computers.

Dangerous territorial specificities became an issue again some time later when the French police started investigating you for promoting suicide through Mouchette.org. That took place in Marseille, the official address of the French artist renting the ‘virtual server’ where you were hosted. You hired a lawyer in Marseille to defend your case, which was the closest you ever got to real crime in your entire life because you were sure the lawyer was more of a criminal than you could ever be. The lawyer wanted to address the question of territory because the accusation and search warrant were issued by the French authorities, but the supposed crime of promoting suicide was committed on Dutch territory where you had a residence permit and created your website. Lawyers in Marseille love crime so much they would use any kind of twisted reasoning to confirm its existence, including jurisprudence on the extraterritoriality of an Internet crime. Ultimately the investigating judge ruled that no crime had been committed and no charges were pressed. The lawyer still billed you for a considerable amount of money on the grounds that he had found the evidence that the servers of Amen.fr were located on German soil (but he didn’t know why).

Now you run your own ‘virtual server’ at Dreamhost.com, an American Internet hosting company based on the West Coast, where business likes to define itself as being a dream – meaning their own, of course. They wouldn’t let you fulfil your own dream of using e-mail functions as a part of your art, because they are a business, after all.

Your ‘virtual server’ is called ‘Bernado Soares’, one of the heteronyms of Fernando Pessoa, the author of The Book of Disquiet. When you’re in trouble with the server or the database, you ask the help of Zenuno, the same Portuguese programmer who helped you before. This new constellation of people and places has a certain sense of poetic ‘disquiet’, bringing you closer to a type of ‘Zen and the Art of Database Maintenance’.

‘I’ is not the ultimate database configuration.

How many times have you dreamt of leaving everything behind, everything that made you who you were, and move to a new, unconnected life, escape the tyranny of your ego and find new love?

You made up a new set of database configurations in charge of saying ‘I’ for you, a virtual character. And then another one. And another….

What was left behind (and never disappeared) was something you could call a ‘you’, a database system exchange of characteristics.

‘You’ is a handy grammatical configuration that can be used for internal monologues since you’re the addressed and the addressee all in one.

When writing a text about personal experience such as this one, ‘you’ embraces the reader inside the experience as if it had happened to him or her.

After all, doesn’t everyone run a database system?

Martine Neddam authors and maintains 9 websites (in 2011)

https://www.neddam.info/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/zen-archive2020.pdf

http://mouchette.org/cv/archive2020.pdf

This text was published in the Mouchette fanzine to be viewed here as pdf

https://www.neddam.info/fanzine/

Online Exhibition “The Recombinants”.

Curator : Madja Edelstein-Gomez .

Can an exhibition be curated by an Artificial Intelligence?

This challenge was taken up by Madja Edelstein Gomez for her exhibition “The Recombinants”.

The participants who responded to an open call were carefully selected by sophisticated algorithms. And now what you experience is a mesmerizing mixture of pictures, videos, sounds, texts situated in an ever-changing screen.

Welcome to the show of the future: The Recombinants.

Even more than their works of art, the personality of the artists, the way they describe themselves and their work, how they show their face or their whole person, all this is being recombined inside the show. On the screen you are offered different perspectives, and with a click, their appearances are slowly revealed to you. Their words will create new meanings in front of your eyes.

Online you will experience a live processing of the data by our artificial intelligence algorithms.

This

individual discovery is left to your patient curiosity and

sagaciousness. Online each viewer will visit a different show, will

travel different spaces and the perspectives of the talent of our

invited artists, which you can also visit one by one. Stand by the

incredible exhibition robots and experience their instant power of

calculation. Guess their moves, anticipate their combinations,

outsmart their artistic intelligence.

Beware, it might shake your

browser and melt your microprocessor!

What artificial intelligence demonstrates is the extreme compatibility of artists. All styles, medias, artistic genres were called for and selected to be recombined in the show. None was too singular, exceptional, or beyond standards. None was too old fashioned, average, ugly, or too unoriginal to be considered as art. The wisdom of artificial intelligence is to dismiss the expected categories of art and to make intuition and sensitivity resurface from within the categorization of art with its historic and social overload. Here viewers are reconciled with pure perception. Here artistic institutions are invited to open up to a new world of art where they may shake off their preconceptions and rethink their notion of what an exhibition can be in the era of the Internet.

Specially for the Art-O-Rama presentation, Madja Edelstein-Gomez chose to record three fifteen minute-long screen captures. They unwind the experience of a live presentation as a recombined hypnotic show of beauty. Here you are invited to create your own trajectory and discover and experience your own show on your computer.

Madja Edelstein-Gomez (born in 1960 in Montevideo, Uruguay) is an independent curator, who has composed several large thematic exhibitions (Bangalore, Buenos Aires, Prague, Tbilisi, Toronto…). Edelstein-Gomez currently lives in Kuala Lumpur and Paris. She is also an activist working with several NGOs. Visit her website: http://madja.net

The online exhibition is produced by Zinc (Marseilles) and supported by : Dicréam-CNC, Château Ephémère (Carrières-sous-Poissy), Espace Gantner (Belfort), Rhizome (New York).

Madja Edelstein-Gomez is the collaborative creation of M. Neddam and E.Guez

This interview of Madja E. G. by Lauren Studebaker, has been published in Rhizome on 25 august 2017. Madja E. G. is the collaborative creation of E. Guez and Martine Neddam.

Madja Edelstein-Gomez is an independent curator and activist, based in Paris and Kuala Lumpur. Edelstein-Gomez has created a new interface for an online exhibition, produced by Zinc, with support from Le Château Éphémère, Dicréam-CNC, L’Espace Multimédia Gantner, and Rhizome. The Recombinants aligns itself with Edelstein-Gomez’s concept of recombinance, a condition of being that she assumes as identity and explores through her recent artistic and curatorial efforts. The Recombinants will show on the front page of rhizome.org from August 25–28th, 2017, alongside the Art-O-Rama fair in Marseille, FR.

Edelstein-Gomez’s concept of recombinance is revealed through the exhibition’s manifesto, which describes a new digital mysticism; one whose text echoes ideas of transhumanism and the simulacrum, with a simultaneous claim to entirely reject these pre-established means of clarification and identification. The manifesto removes itself from the vernacular application of the term “recombinant” (one tied to genetically modified organisms). Instead, the recombinants’s materials are described to be the result a form of data-splicing that removes any disparity between the data anatomy of digital datasets and organic DNA, which are explained to be constantly rewritten, or “recombined” in a cycle of constant rebirth and in the form of an eternal return. The manifesto claims many things the Recombinants are not; there are direct rejections of being merely cyborgs, replicants, mutations, humans, or computers, and the Recombinants reject any adherence to the past or future. From an outside perspective, the manifesto is mysteriously ambiguous, as the Recombinants claim to exist as nothing and everything at the same time.

Upon entering the online exhibition, the viewer is greeted with a slowly-moving landscape of colliding image-planes and broken and disrupted bits of sound. The viewer is encouraged to navigate through the use of a series of geometric buttons that reveal text, change the presentation style, and provide links to individual artist’s profiles. In the exhibition’s press release, it is revealed that the online presentation is an AI-generated recombination of the submitted works, being constantly processed live and presented differently for each viewer, with an audacious claim to be the “show of the future.”

I spoke with Edelstein-Gomez to discuss her exhibition and curatorial practice in the hopes of expanding upon her understanding of the recombinant existence and its applications to this online exhibition format.

Lauren Studebaker: Usually, we’re familiar with the term “recombinant” in its applications to genetics and biology—GMOs, gene-splicing, etc. In the Recombinant Manifesto, this application of the term is mentioned, but transcended. Could you introduce your concept of the Recombinants?

Madja Edelstein-Gomez: Rerecombinance, recombinance, recombinanciation, recombing… What can I say about recombinance, except that doesn’t easily lend itself to commentary… Touch it, refer to it, think about it and you get affected, contaminated, it’s an autoimmune remedy to every disease. Recombinance recombines itself by using everything around it. Oops, you just got recombined.

LS: How did you come into the realization of recombinance?

MEG: One day I became a Recombinant.

No.

I always have been a Recombinant.

And it was not just me. I know there are many Recombinants out there.

I realized that something had occurred that should have killed me or make disappear. It was a like a system error in an operating system, or a genetic modification in a living being. But that thing wasn’t new, it was always already there, encoded inside of me.

It’s quite hard to explain. Instead of being afraid of it, I tried to claim it, it inspired me this manifesto.

LS: What influenced your development of this recombinant philosophy?

MEG: It was shattering and some twitching slightly resonated with it. And once it blasted, I encountered tiny skewed elements inside my existence.

In biographical terms, I could have said “this” and “that” happened to me. But I’d rather not express what happened within a timeline, with a “before” and an “after.”

I now know it was always there.

Read more about this “moi” here.

But don’t worry, I’m not some sort of psycho freak. When needed, there can be a regular bio and a presentation of myself as an online curator that fits the bill, like what Le Zinc in Marseille has published.

LS: How does the recombinant philosophy tie itself into the presentation of works online and how is the exhibition format of exclusively digital means of presentation in alignment with the recombinance?

MEG: Online, all data generates more data.

Ad infinitum.

View any odd webpage and your viewing data has been recorded by numerous systems along the line, the cookies on your hard disk, your internet provider, your social networks, every online activity leaves slimy, greasy, dusty fingerprints made of data, that proliferate into big datasets, and when analyzed, produce more data, etc…

LS: A realization in the Recombinant Manifesto surrounds the idea of collapse of the concept of past and future, a rejection “of everything post- and trans-.” As a curator, how would you say this position of recombinance informs your selection of works and philosophy of contemporaneity in the context of an exhibition?

MEG: A non-human narrative doesn’t relate to recombinancial time or category and doesn’t relate to post-something or trans-something. Inside it, you get exposed to sequences of data that will rewrite you in such a way that doesn’t let you refer to an existing model of reference.

And yet, what we are doing is simply sending out an open call for an online show. It is our way to set into motion the possibility of a recombinant narrative written by the machine herself. The narrative of data being mined and reminded.

LS: So, the idea of recombinance is tightly aligned with data ontologies? Could you then talk a bit about the presence of recombinance, or the recombinant action, in digital artmaking?

MEG: Artmaking itself is not the question really, digital or not. Art is not necessarily something you “make,” so I’m not talking about artmaking. Art is something you “name,” not something you “make.” All you need for something to be art is to be recognized as such, to be named it as such, and it becomes art.

The question “what is art?” ran through the whole twentieth century. Until we found out that art was nothing but a question.

Now, in the twenty-first century, we have the answer to “what is art?”: Art is a Question.

A question is a recombined statement. For example, if you recombine “This is art,” it becomes “Is this art?” The question mark signals that you have opened the signification to endless possibilities, and you have generated the desire for something, the inextinguishable desire for an answer, a hole inside a meaning.

Now imagine you go further into recombinance by shuffling every single letter of this chain of characters. You have generated a multiplicity of new meanings all derived from this dataset, like “a tart wish,” “war at hits,” “it shat raw”… and many many meaningless combinations. You have created an infinity of littles holes of meaning, a lace of meaninglessness all intertwined around that big question. These are the generative powers of Recombinance, and this is how I am curating.

LS: Then what hand does curating the results of the open call have in the equation? As one who identifies as recombinant, how does your curatorial practice differ from a more traditional model?

MEG: I see curating in general, traditional or not, as “a throw of dice.”

Chance is the main factor.

Curatorial explanations are nothing but a layer of varnish over it.

“Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard.”

“A throw of dice will never abolish chance”, said the French poet Mallarmé, as he scattered the words of his poem across the page with plenty of empty space around the words. That was a founding act in poetry in 1897, and if you ask me, the very first act of Recombinance also.

One hundred and twenty years later, commentators still wonder if what scatters the words of Mallarmé is not a hidden code, yet uncracked. Quentin Meillassoux in The Number and the Siren argues that there must be a code, but the encoding of the poem is incomplete, and that is precisely how Mallarmé wanted it: an incorrect code.

Is Recombinance a form “curating by numbers?”

Is there a curatorial algorithm at the heart of my practice?

If there is a code, I myself am included in that code, I am just a piece of that DNA, and whatever I change in it, changes me, in an incomplete way.

LS: Does the possibility of anonymity from online submissions (or the digital in general) enhance the recombinant philosophy?

MEG: Anonymity is not an issue at all. A name is just an element of a dataset, and not the most interesting one.

Besides, when you submit online, you do it with your own chosen name.

What you might not know is that when you post your data, is that you get your personal exhibition on the spot, as the first display of your recombined art. This display remains available and you can share it online with everyone. This is the reward of trust.

Look at some personal exhibitions available here from Guido Segni,Chloe Cheronnet, Garrett Lynch, and Anne Pfff.

In our big exhibition which will premiere in Art-O-Rama in Marseille in 25 August the names will not disappear. They will be recombined together with the works.

LS: On both your personal website, as well as in the Recombinant Manifesto, you recognize psychic energies, telepathy, spiritualism, and the paranormal as different manifestations of recombinance. As both an artist and curator working with the internet and developing technologies such as AI (in your chatbots, for example) as a means of production and exhibition, how do you view the collective and ephemeral condition of the digital in comparison to these more mystic ideas?

MEG: Once you start questioning the premises of your own bodily existence there is no way back. I am the product of a communication energy, just as much as you are.

Life is but an exchange of messages.

And it’s pretty much the same as what we are doing now: exchanging messages.

IMPAKT EXHIBITION: TRUTH THAT LIES

Curated by Renata Šparada & Irena Borić,

9 February – 17 March 2019,

IMPAKT Center for Media Culture, Lange Nieuwstraat 4, Utrecht.

How we are being misinformed in the age of information.

Artists in the exhibition: Keren Cytter, Omer Fast, Harun Farocki, Sharon Hayes, Hrvoje Hiršl & Luis Rodil Fernández, Martine Neddam, Erica Scourti, Mladen Stilinović and The Yes Men

Social media sites and search engines are the key ingredients of the change from the manipulative form of propaganda of the past to the prevalence of the Post-truth paradigm of the present. How are words and ideas used to obscure and manipulate? The exhibition and panel discussion of Truth That Lies look at the different political and cultural strategies that have been used in our Post-truth reality and in our recent history.

Inspired by George Orwell’s prescient novel 1984, the events take the shape of the two agencies in The Ministry of Truth, the propaganda agency of 1984’s dystopian government: the Fiction and the Records Department. The Fiction Department is represented by Truth That Lies, an exhibition exploring a use of language through gesture, manipulation, hate speech, algorithm, propaganda, make-believe or tautology.

The Records Department is mirrored in a panel called War on Facts. This panel will be organized on 8 February, prior to the opening of the exhibition, and it will address misinformation, alternative facts, fake news and information manipulation.